For the past two years, a disturbing graphic about U.S. health spending has been circulating on social media. It shows the United States’ life expectancy and per capita health spending compared to other major countries. The U.S. diverged from the rest of the world in about 1980; life expectancy gains faltered while health costs soared. The point made by this graphic seems to be that health spending in the U.S. has been a terrible investment.

Source: Our World in Data

High Health Spending is a Symptom, Not the Disease Itself

Too many policymakers treat the health system like an enormous black box where money goes in, and health comes out the other end. They assume that if less money is funneled in, the system will somehow optimize itself.

This is a flawed model because the intervening variable between spending and health is a markedly unequal society—one that damages its citizens by neglecting their core needs. In addition to leading the world in health costs, the U.S. also exceeds most comparable nations in suicides, obesity, drug overdoses, homicides and maternal deaths.

The heart of the problem is a misallocation of societal resources. In her book The American Healthcare Paradox, Elizabeth Bradley showed that the U.S. was comparable to peer nations in combined healthcare and social infrastructure spending. However, the U.S. markedly underspends on social infrastructure and support for families (e.g., addressing food insecurity and homelessness, drug abuse treatment, paid maternal leave, etc.) and, in turn, outspends them in health services.

Source: OECD, OECD Data Explorer, Accessed July 1, 2025

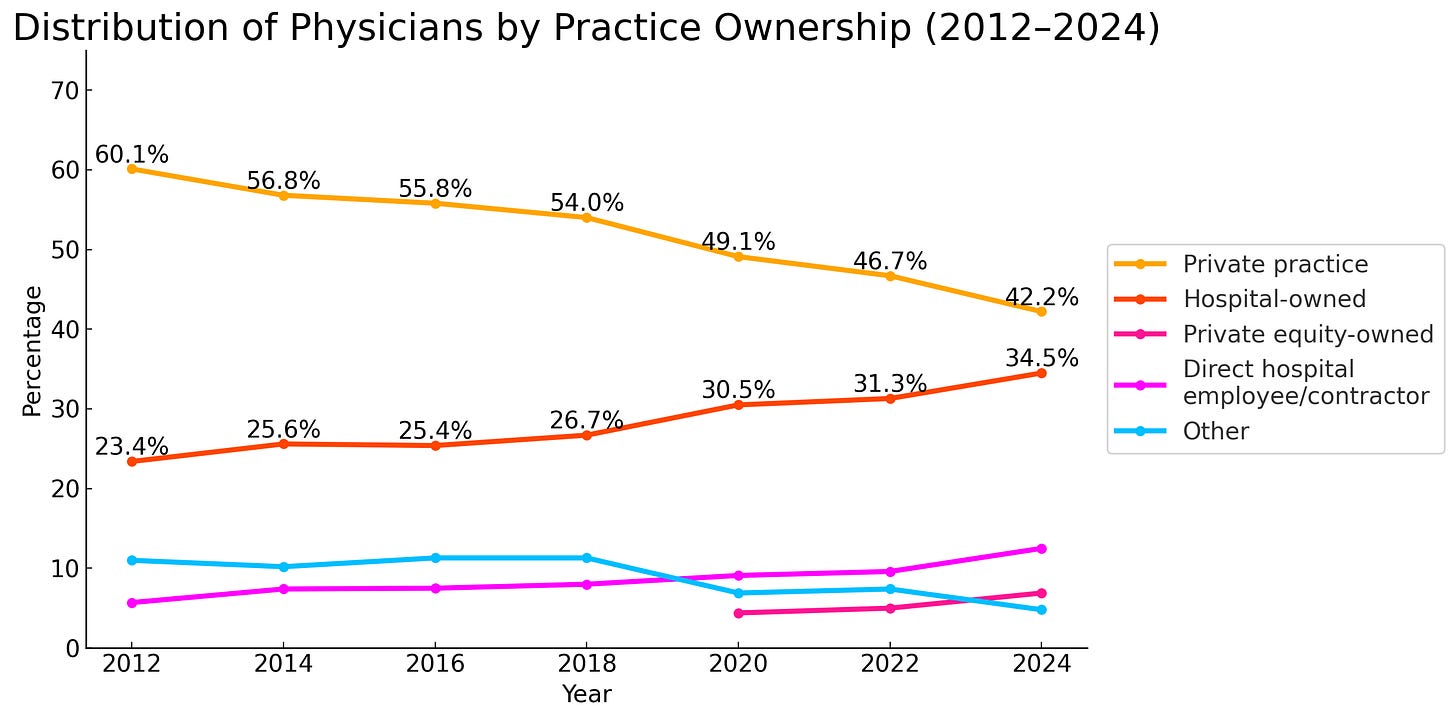

This same shortsighted misallocation also occurs inside the health system. For more than two decades, Medicare payment policy has starved the primary care physicians (as well as nurses and home health aides) who help manage patients’ serious clinical risks and keep them out of hospital emergency departments. Medicare, the largest single payer of physician services, has allowed Part B physician payment rates to lag cost increases in medical practice by 55%, and lagged general inflation by more than 30% over the past 25 years. This had the predictable effect of undermining private medical practice and driving physicians into hospital employment or corporate practice funded by private equity firms.

Source: AMA, “Policy Research Perspectives--Physician Practice Characteristics in 2024: Private Practices Account for Less Than Half of Physicians in Most Specialties,” 2025

The result: critical shortages of primary care physicians in both inner cities and rural areas. The Association of American Medical Colleges estimates the U.S. will face a shortage of up to 40,000 primary care physicians by 2036. Overall, the nation could be short as many as 86,000 physicians across all specialties by 2036. A major driver: 23% of all practicing physicians in the U.S., including primary practitioners, are over the age of 65 (36% of practicing psychiatrists) and likely to retire within a decade.

Over the same period, hospitals have filled unmet physician needs in their communities, but at enormous cost. By early 2025, the average gap between a hospital-employed physician’s salary and the revenue they generate, after overhead, exceeded $300,000. Without hospitals, the northernmost 300 miles of the U.S. would be a physician desert (and many of the hospitals would have already closed). Yet, the federal subsidies that hospitals use to offset some of these losses-= facility fees and clinic charges (including so-called “site of service” payments)- are controversial and likely to be reduced by Congress in future years.

OBBBA Will Accelerate This Flawed Investment Pattern

Unfortunately, the recently enacted fiscal 2026 federal budget will worsen the misallocation outlined above. While the legislation leaves Medicare largely untouched, it cuts nearly $1 trillion from future Medicaid spending. Medicaid currently covers about one in four Americans. According to the Congressional Budget Office, funding reductions in OBBBA will result in 10 million people losing health coverage.

This estimate does not include an additional 5 million people who are expected to lose Health Exchange coverage if Congress does not extend the COVID-era enhanced subsidies that boosted enrollment to almost 24 million in 2023. The reduced subsidies are expected to result in a 75% increase in premiums for those who remain enrolled in the Exchange, further reducing enrollment. So together, these Congressional actions could increase the ranks of the uninsured to over 40 million, taking us back to where we were at the beginning of the millennium. Congress is in the process of repealing most of the ObamaCare coverage expansion.

The bill also reduces Medicaid state-directed payments to private Medicaid managed care plans and rolls back provider taxes, which provided funding that states have used to true up inadequate Medicaid payments to hospitals and physicians. Combined with the expected increase in the uninsured population, these changes will add an estimated $443.4 billion in uncompensated hospital care over the next 10 years. Much of that cost will be passed on to employers through higher employer-based insurance premiums.

Critically, OBBBA will exacerbate the structural imbalances in the health system discussed above. Medicaid is the largest payer for substance abuse services in the U.S. At least 1.6 million Medicaid recipients receiving substance use disorder treatment are likely to lose eligibility because of OBBBA’s Medicaid changes, potentially disrupting access to treatment and medications that keep them off opioids. Lives will be lost, and more individuals will end up in ambulances headed for hospitals.

Medicaid is also the largest payer for nursing home services in the U.S. Reduced Medicaid funding will likely push many marginal nursing homes into bankruptcy, making it increasingly difficult for hospitals to place patients who are not acutely ill but are too sick to return home into long-term care.

Likewise, Medicaid is the largest single revenue source for the nation’s 1,359 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), which care for more than 34 million Americans regardless of their ability to pay. Medicaid payments account for 60% of FQHC revenues. Combined with the $11 billion in ‘clawed-back’ funding for state and local public health agencies, these reductions will further compromise the public health safety net, leaving hospitals even more isolated as the most expensive providers in their communities.

Michigan is a Microcosm of Health System Balance Issues

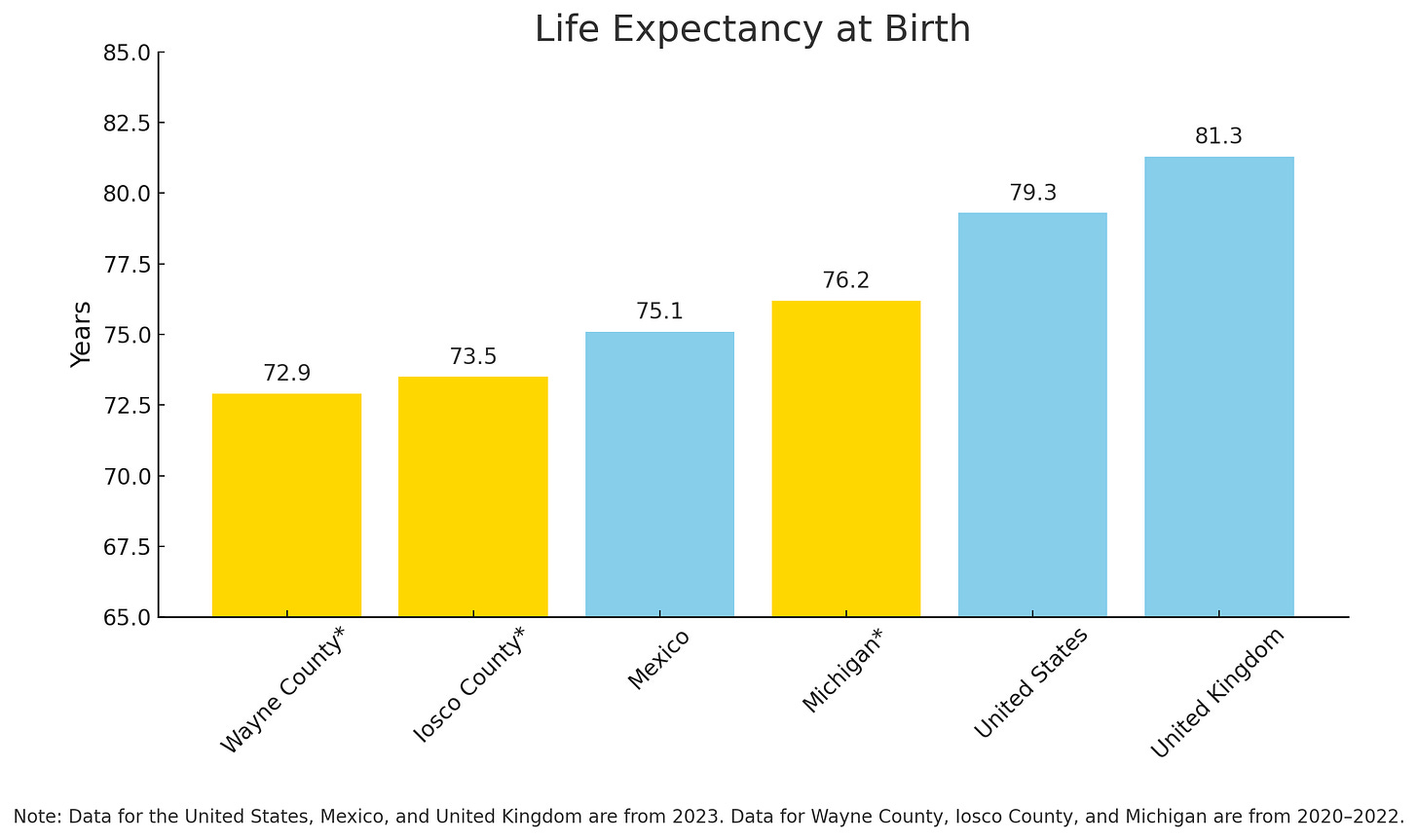

Michigan exhibits all of these problems. Both its urban and rural communities struggle to provide adequate social and human services. The result is far lower life expectancies than should be expected in a free and prosperous nation. Life expectancy in Michigan is a full three years lower than that of the US as a whole. Life expectancy in rural and urban Michigan counties is lower than that of Mexico!

Source: County Health Rankings and Roadmaps; Institute for Demographic Studies

In both urban and rural communities , the hospital has become not only the largest employer but also the de facto public health system for the surrounding region. Michigan has the highest hospital readmission rate for Medicare patients in the nation, as unstable patients overwhelm their families and return to the hospital. Not surprisingly, metro Detroit ranks among the highest in the nation for Medicare inpatient admission rates and hospital days per thousand residents. Detroit also has the ninth-highest emergency room (ER) visit rate for older adults in the U.S.

It is tempting—but wrong—to blame the care system for this state of affairs. Overall, Michigan ranks 31st in the nation in per capita health spending, according to KFF, but 43rd in “other health, residential and personal care,”the closest category to Elizabeth Bradley’s concept of social infrastructure spending.

By the time a patient reaches the ER, it is too late to fix the underlying health problems that led them there. Poverty and lack of opportunity set people up to fail. Alongside the primary care problem, poor nutrition, family instability, and other social factors increase health risk. People fall through multiple cracks into the hospital, which is open 24/7/365, and mandated by federal law to provide care. Reducing these admissions is one of many ways communities can work with their care providers to contain health costs.

Follow the Money (or Lack of It)

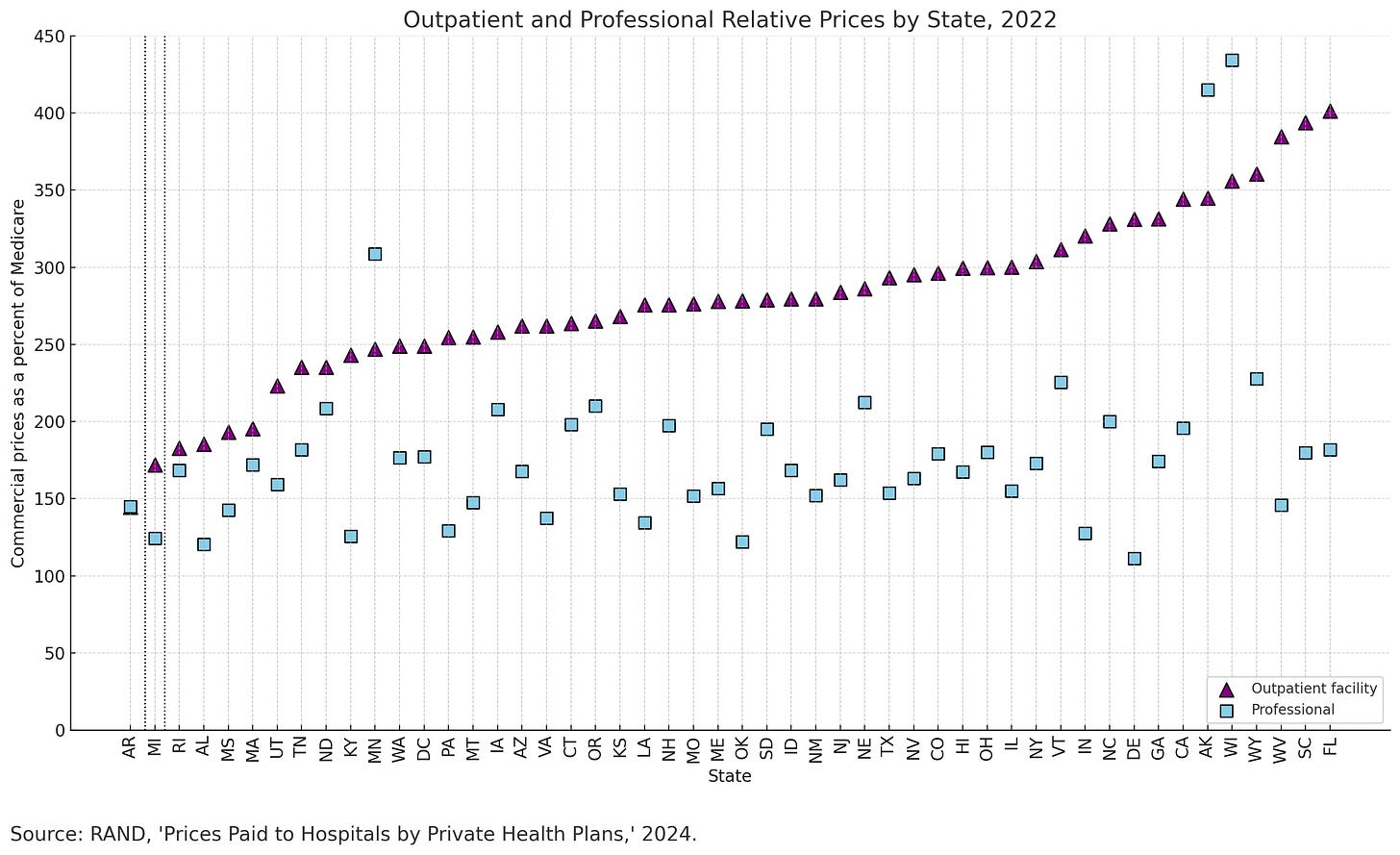

It should surprise no one that states with low payment rates for physician services by commercial insurers—the only possible source of funding to offset federal shortfalls— are struggling with health costs. Michigan’s relative commercial payment rates for physician and clinic services are among the lowest in the nation. Only Arkansas pays less for hospital outpatient services in the U.S.

*Note: The relative outpatient price for AR is nearly identical to the relative professional price, so appears to be hidden in this chart.

If the goal is to avoid expensive hospital based acute care, stinting on physician and ambulatory care payment is the textbook definition of a false economy. These low rates make it difficult for independent physician practices to survive, forcing practitioners into higher cost settings. They also penalize hospitals for moving high-tech procedures, such as joint replacements, into ambulatory settings, where care is quicker, safer and far less costly to employers and patients alike.

Crucially, Michigan had the lowest rate of health spending growth in the nation (4.9% annually from 1990 to 2020). If Michigan’s health costs had grown at the national average annual rate of 5.7% for those 30 years, its health spending would have been $25.9 billion higher, or 26% more. Michigan is also 47th in hospital profit margins. So pointing to Michigan as an example of out-of- control health spending ignores the national context.

What Can Be Done About These Problems?

Reducing demand for the most expensive services offers the greatest leverage for lowering health spending. Reducing avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions should be the core focus of any effort to improve affordability of care.

First, we must move dollars forward—toward the patients before they become patients. This means providing non-incremental payment increases both from commercial insurers and Medicare for:

· Primary care physicians

· Substance abuse treatment programs

· FQHCs

· Ambulatory surgical and imaging services

We also need to markedly increase payment for mental health services, both in person and virtual, particularly in inner city and rural areas that face severe shortages.

Second, we must advocate for federal policies that take pressure off commercial health insurance rates. This means that employers, public health advocates, physician organizations and other stakeholders must advocate aggressively to reverse the Medicaid “reforms” enacted in July 2025 by Congress before they take effect in 2028.

As written, the new federal budget would cut more than $6 billion in Medicaid funding for Michigan hospitals over the next decade. The costs of these Medicaid reductions will directly affect employers’ health insurance premiums in future years. In addition, employers and providers together must advocate for revisions in the Medicare Part B fee schedule for primary care physicians to prevent further strain on frontline care.

Third, Michigan hospital systems have created extensive care management infrastructure to support both provider-sponsored health plans as well as value-based care risk-sharing arrangements with commercial insurers. Health systems can use this care management infrastructure to help identify in advance, by coordination with FQHCs and primary care practices, patients at risk for hospitalization and address both medication and care gaps to keep them out of the hospital. This will be particularly important for the millions of persons who lose Medicaid or ACA Health Exchange coverage under OBBBA, since the increased cost of caring for the uninsured will increase pressure on private health insurance rates.

A related opportunity is reducing maternal mortality. More than a decade ago, California reduced maternal mortality by nearly half through a structured collaboration between state public health, FQHCs, the obstetrical community and hospitals. They did so by identifying pregnant women at risk and attacking leading risk factors through protocols for physicians to aggressively manage them. The result: death rates rivaling those in the European Union and many lives saved. Michigan is well-positioned to replicate California’s model and save more mothers’ lives.

Fourth, health systems can collaborate with health plans to reduce the administrative overburden that drives up hospital and physician operating expenses and diverts scarce caregiver time into documentation and fiddling with their electronic records. Researchers have found that clinicians now spend as much time documenting care as delivering it. McKinsey estimates that better coordination of health insurance payment processes between payers and healthcare providers could save $265 billion.

Though the recent Change Healthcare cyberattack raised questions about the safety, and thus feasibility, of a single national health insurance claims clearinghouse, standardizing data requirements across payers could still significantly reduce administrative costs.

Today, each insurer has different requirements and payment criteria. Extending “Gold Card” programs (which bypass case-by-case prior authorizations) to entire institutions with thoughtful, conservative care patterns could markedly reduce administrative costs as well as increase available physician practice time. Giving physicians back one day a week for patient care is the most sensible strategy for alleviating the looming physician access crisis.

Fifth, health systems should provide “concierge service” for self-funded employers, helping to resolve payment controversies while coordinating care and improving access for employees at risk of serious health problems.

Health insurance middlemen are too far removed from the point of care to meaningfully affect employer access and costs. Presently, 79% of all businesses with more than 200 employees no longer shift insurance risk for health coverage to health plans. Rather, they retain the risk and hire third-party administrators to manage their health coverage on an “administrative services only” (ASO) basis.

Self-funded employers increasingly feel like second-class customers compared with insurers’ fully insured clients. Several large employers have sued their ASO carriers for poor contract performance. Health systems, where services are actually delivered, have the greatest cost leverage and can help fill this gap, directly addressing employer concerns.

Conclusion

The only way to achieve sustainable cost stability and high-value care is to correct the funding imbalances and poor coordination that drive avoidable health costs. COVID-19 destabilized the entire public health and care ecosystem, which are still recovering from the damage done.

But the underlying society in which the health system operates remains profoundly out of balance, creating both excess administrative expenses and shortages of frontline care—conditions that lead directly to avoidable hospitalization.

This, not inflation or “waste, fraud and abuse.” is the real cause of health system dysfunction, excessive cost and lost lives. Recent federal reductions in public health funding, combined with Medicaid cuts and coverage losses under the recently passed federal budget, will only worsen this misalignment.

Call to Action

These problems will not fix themselves. The major players in the health system must act collaboratively and proactively to address them.

-Health insurers must markedly reduce the case-by-case second-guessing of clinical decisions and reduce the administrative burden they impose on clinician and health facilities. In short, they need to stop practicing medicine by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm. They must markedly improve payment for front-end health services, such as primary care, ambulatory services, behavioral medicine and community health. And they must pass the resulting savings from these actions onto their employer customers.

-Health systems must move aggressively to use their data systems and primary care cadres to identify and manage health risks before patients end up in the ER. They must identify ways in which AI can improve responsiveness and productivity and consequently reduce their administrative overhead. They must also move aggressively to ease their physicians’ administrative burdens and thereby reduce waiting time for appointments as well as improve follow-up care.

-Legislators and Congress must repeal the ruinous reductions in state matching formulae for Medicaid under OBBBA and reverse the “re-welfarization” of the Medicaid program by making it easier, not harder, for low-income Americans to access. They must stop starving frontline caregivers by reforming the Medicare Part B physician payment system and moving dollars forward toward patients. They must also reverse the catastrophic reductions in public health funding for state and local health departments and FQHCs.

-Self-funded employers should reduce their dependence on third-party administrators for managing their health-benefit cost risks and work directly with local health systems to identify and reduce barriers to care and resolve cost issues quickly and transparently.

-Everyone needs to stop pointing fingers at others and work collaboratively to make care more responsive and affordable. Only through meaningful collaboration can patients and their families get the care, support and answers they need to manage their health risks.

My old friend and colleague, Jeff Goldsmith, is right. There is an enormous untapped opportunity to avoid costs and improve lives by better managing chronic illnesses, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Too often the provider community asks “who’s going to pay for” care management in the low socioeconomic population. We’re not keeping score properly. Health systems are paying for not doing it better…in the form of avoidable (under-compensated) ER visits and low severity inpatient admissions. Tertiary medical centers that have strained capacity have opportunity costs, unable to accept higher severity transfers. We need to stop asking where the new revenue will come from and start measuring avoidable losses. Money not lost is as green as money made. Turn our attention from solely chasing private sector market share to managing complex and chronic illness - including and maybe even especially in the less affluent portions of the service area.

Jeff’s long history in helping many of us through his consulting, my experience with him in various ambulatory settings in the 80s, gives him credence in his overview of our health care issues

In my UCLA EMPH class I cover all of these topics; while promoting global capitated risk in the delegatesd model that frees up monies to spend on SDOH and prevention and paying primary care physicians more that the average to foster primary care; and coordinated medical care

And emphasize this being done in (truly) integrated health systems ( which includes physicians and emphasis on ambulatory care)

FFS medcine does not free up monies for SDOH, at least in physcian offices where all monies left over after overhead is physcian income

Whereas in medical groups taking risk. And doing it well, like ChenMed and others , reduce hospital and ED visits creating a either shared or global risk pool, which can be millions of dollars, that can be dispersed to provide more income to primary care providers, transportation, food, health and behavioral health education (well child, prenatal, smoking cessation, diet.. counseling… I know we did, at least in some of my medical groups

Kaiser is often considered a gold standard in the VBC model as my example of a fully integrated health system (because it includes the NFP health plan( whereas most IHS, don’t have the health plan and many are dumping them ( very capital intensive and many competing needs in the systems)

In essence the countries cited are capitated as the government sets the funding ( the NHS is truly socialist, others are not)

There limit on health spending allows more to social needs

There are some glaring issues as far as health spending which I do not see being tolerated here:

Physcians earn half of what they do in the US; accounting for our excess of cost by 15% according to one study

Same amount applies to nurses

And about the same to our excess administrative costs

Also since 70-80% of our health costs are directly related to lifestyle; mainly diet and physical activity; there has to be more accountability to personal control… it can’t continue to be we can let things go and the health system will fix it .. at tremendous cost

Since we are as a country in major debt, the current focus is to cut costs, increase revenues which, as Jeff points out has a major detrimental effect in what healthcare professionals feel are our needs

I am glad Jeff continues to speak out